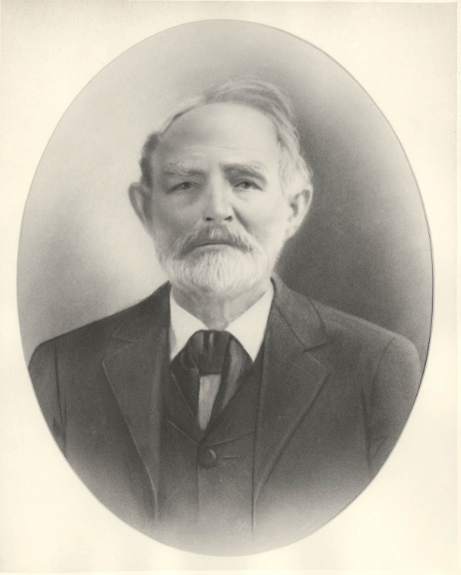

Henry Wickenburg, Town Founder

A German immigrant, Henry Wickenburg was born Johannes Henricus Wickenburg, on November 21, 1819, in Holsterhausen, Germany, outside the city of Essen, and left Europe in 1847 to come to the United States. No one knows exactly what he did after arrival here, except that he spent some time in California before coming to Arizona either 1861 or 1862. After a brief stint at Fort Yuma and then La Paz, where he tried his hand at placer mining, Wickenburg moved on to central Arizona. He eventually settled in Peeples Valley, where he was living in 1863, the year he undertook his most famous prospecting trip.

Hearing of gold prospects in the Harquahala Mountains, Wickenburg set out from his ranch with two other men, E.A. Van Bibber and Theodore Green Rusk, on a trip to the mountains. On their way back from the Harquahalas, where they failed to discover anything of particular interest, Wickenburg became interested in a prominent white quartz ledge that protruded from a ridge of low mountains just west of the Hassayampa River. His companions did not share his enthusiasm for the location, however, and the three men returned to their homes without filing a claim.

Wickenburg, though, remained convinced that the ledge offered promise as a gold mine location. Within the month, he returned to the site alone, this time finding rock samples that bore evidence of gold. When he showed the samples to his two erstwhile companions they agreed to return to the site for another inspection. This time they were impressed, and together they filed a location notice for the mining claim, which they called the Vulture.

Exactly how that name was applied to the mine, and to the mountains at whose base it was located, is shrouded in legend. According to one version, Wickenburg had seen a vulture perched nearby while he was prospecting the area; according to another, he shot and killed a vulture perched on the quart ledge, and then discovered the valuable ore samples when he went to inspect his prey. Henry also gave a version of his own story to one newspaperman in 1897; “I always like short names, and it just came into my head to call it the Vulture. The rock was very dark and it did not look much like quartz.” Whether this is the “true” version is impossible to verify; Wickenburg appears to have related several versions of the story himself – or, at least, his listeners seem to have heard what they wanted.

At any rate, neither Wickenburg nor his companions did anything to develop the mine at first, despite their initial enthusiasm about the claim. Van Bibber and Rusk actually left the area, leaving Wickenburg alone and living in very modest circumstances on the banks of the Hassayampa River several miles from the claim site. Eventually, even Wickenburg left, returning in May 1864 to find the site deserted and showing no evidence that anyone had tried to work the claim. He filed a second claim with four new partners, and together they organized the Wickenburg Mining District, registered their claim at Prescott, and started development work on the mine. After digging out a ton of ore, which they laboriously hauled to the Hassayampa River, Wickenburg and his partners built an arrastra, or stone ore-grinding stub, and began processing the rock. Their labors yielded a promising amount of gold, although like everything else having to do with the Vulture Mine, exactly how much is disputed. Even at a low figure, it was a substantial sum of money, enough to encourage Wickenburg and others to continue their development work – and enough for Rusk and two other men to file a lawsuit against Wickenburg alleging that they were being cheated out of Rusk’s one-third interest in the mine. The suit, which was the first piece of mining litigation heard in Arizona’s territorial courts, argued that the original claim filed by Van Bibber, Rusk, and Wickenburg was still valid, and Rusk’s sale of his interest to the two men gave them part ownership of the Vulture Mine. Fortunately for Wickenburg, the plaintiffs lost on the grounds that he and his two original companions had never properly registered their claim at the territorial capital.

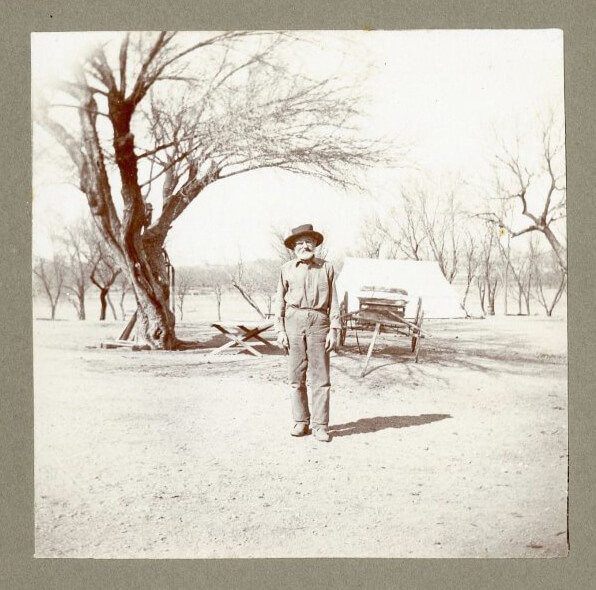

Free of any cloud over his ownership of the mine, Wickenburg set about promoting the Vulture’s full development. Rather than work the mine himself, Wickenburg let others take out ore in return for a payment of $15 per ton. By late fall, operations at the mine and on the banks of the Hassayampa were in full swing, with various groups of miners taking out as much as seven hundred dollars in gold each day. By 1865, about forty arrastras were in use along the riverbank. This process, which was first developed by Spanish miners, required no machinery and thus was well adapted to the conditions that prevailed at the Vulture, whose isolation made the importation of processing equipment an expensive and time-consuming undertaking.

As word of the mine and its development spread across the country, it attracted not only miners but also journalists. One correspondent, writing for the Hartford Evening Press in Connecticut, predicted that “a stream of gold will our from the Hassayampa when the quartz mills arrive, and all this tedious process is done by the power of steam. There is no portion of the mineral region so favorable for the working of a large mine.” His prophecy was realized for the most part toward the end of the summer of 1865, a small stamp mill was erected on the opposite side of the river bottom from the present-day Remuda Ranch – giving the miners an easier and more efficient mechanism for reducing, or crushing, the ore prior to amalgamation.

With ore valued as high as $80 per ton, the Vulture Mine was bound to attract the attention of investors. In late 1865, Wickenburg who had acquired sole ownership of the Vulture claim by this time sold his interest in the mine to a group of New York men led by Behtchuel Phelps. After paying Wickenburg $25,000 for several hundred feet of the Vulture lode – the most valuable part of the claim – as well as the stamp mill, which Wickenburg had recently taken over, the buyers incorporated the Vulture Mining Company and began placing orders for new ore processing machinery. (From the Book: The Town on the Hassayampa – Mark E. Pry)